The Red Sea Crisis and Its Economic Spillovers for South Asia

Introduction

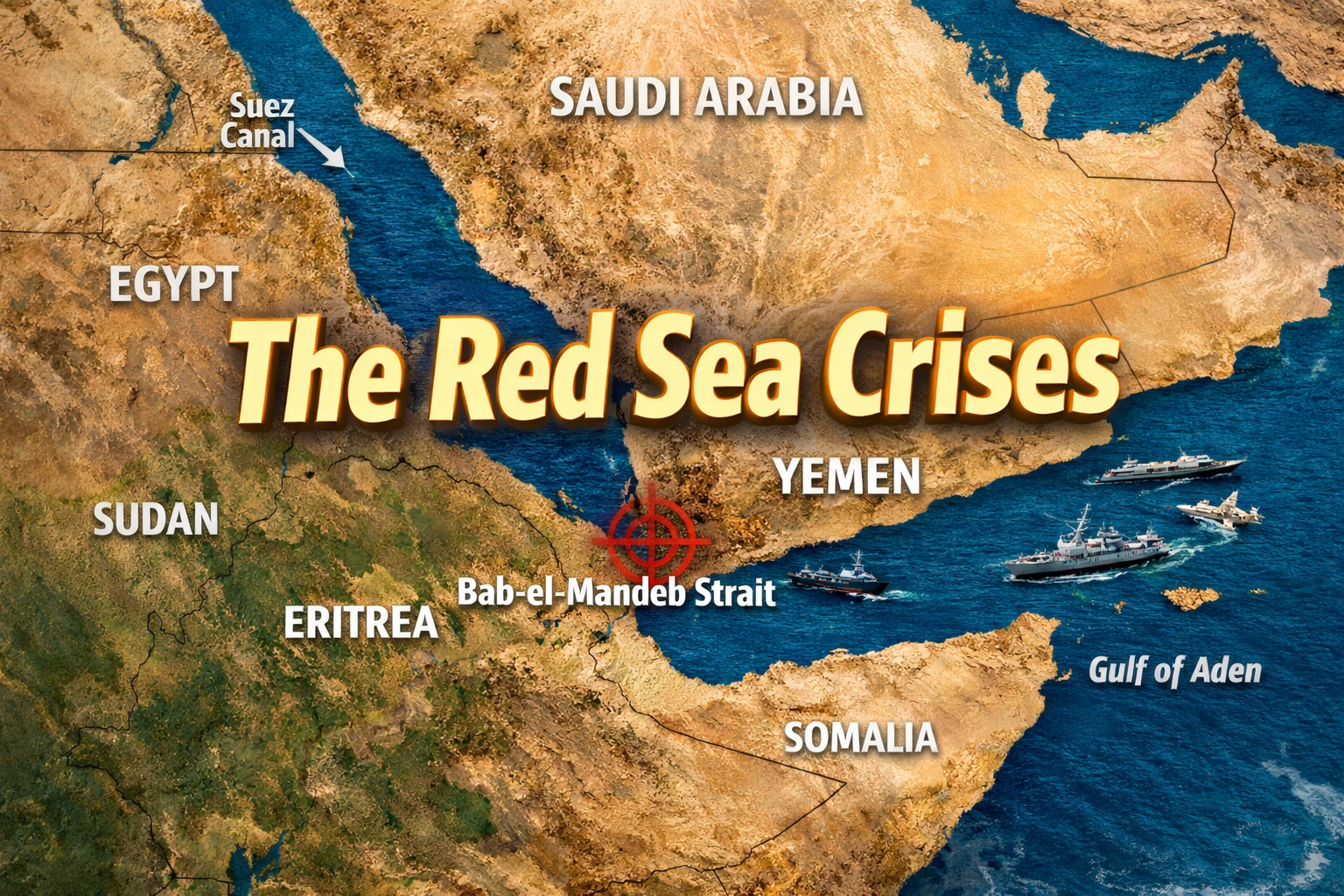

The Red Sea occupies a central position in the architecture of global trade. Connecting the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal, this maritime corridor functions as one of the world’s most vital commercial arteries. Approximately 12–15 percent of global trade and nearly one-third of global container traffic transit this route each year, making it indispensable to the functioning of international supply chains.

Since late 2023, the security situation in the Red Sea has deteriorated sharply due to repeated attacks on commercial shipping, largely attributed to Houthi forces operating from Yemen. These attacks, involving missiles, drones, and boarding attempts, have dramatically altered the risk profile of the region. By early 2024, major shipping companies began suspending transit through the Suez Canal and rerouting vessels around the Cape of Good Hope.

For South Asian economies—particularly Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh—the Red Sea crisis has not merely been an external shock but a structural stress test. These countries rely heavily on maritime routes for both imports and exports, and their development strategies are deeply embedded in global value chains. This crisis exposes deep vulnerabilities in how South Asia connects to global markets.

The Strategic Importance of the Red Sea and Bab-el-Mandeb

The Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, located between Djibouti and Yemen, is only about 20 miles wide at its narrowest point. Despite its small geographic footprint, it connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and the broader Indian Ocean, forming the shortest maritime route between Asia and Europe.

Historically, the security of this passage has been a major concern for global powers, as it directly affects energy shipments, containerized trade, and bulk commodities. Around 8–10 million barrels of oil and large volumes of liquefied natural gas transit the Red Sea daily. Any prolonged disruption therefore has inflationary, strategic, and developmental consequences.

Unlike earlier piracy threats in the region, the current Red Sea crisis is embedded in a wider geopolitical confrontation involving Yemen, Israel, Iran, and Western naval coalitions. This transforms a logistics challenge into a sustained security dilemma.

Shipping Rerouting and the Transformation of Global Logistics

In response to heightened security risks, shipping giants such as Maersk, MSC, Hapag-Lloyd, and CMA CGM suspended Red Sea transits and redirected vessels around the Cape of Good Hope. This alternative route adds approximately 3,500–6,000 nautical miles and increases voyage durations by 10–15 days.

The implications are profound. Fuel consumption has surged, war-risk insurance premiums have risen, and freight rates on the Asia–Europe route more than doubled in several segments. Containers are now tied up longer in transit, creating shortages in exporting countries like Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

This shift has eroded the efficiency gains of just-in-time logistics and pushed global trade into a risk-managed, security-driven model.

Pakistan: Trade Dependence and Macroeconomic Fragility

Pakistan conducts over 95% of its trade by sea. Rising freight costs have inflated import prices and transmitted imported inflation into the domestic economy. This has worsened Pakistan’s already fragile macroeconomic environment, characterized by high inflation, fiscal stress, and balance-of-payments constraints.

Energy imports are especially sensitive. Volatility in Brent crude prices linked to Red Sea instability has increased Pakistan’s fuel bill and placed additional pressure on foreign exchange reserves.

The textile sector—accounting for nearly 60% of exports—has suffered from late deliveries to European buyers, resulting in penalties, lost orders, and reduced competitiveness.

India: Trade Costs and Strategic Naval Engagement

India’s logistics costs for engineering, pharmaceutical, and agricultural exports have risen by 20–30%. While India has greater economic resilience, these increases reduce exporter margins and weaken competitiveness.

India has expanded naval deployments to escort commercial shipping in the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Aden. This reflects the growing securitization of trade routes and the fusion of economic and strategic policy.

Bangladesh: Garment Dependence and Supply Chain Vulnerability

Bangladesh’s garment sector accounts for over 80% of export earnings. Delays in raw material imports and finished goods exports have disrupted seasonal fashion cycles, threatened employment, and weakened foreign exchange inflows.

Retailers operate on strict seasonal calendars, and late shipments often lead to discounts, cancellations, or long-term loss of contracts.

Energy Markets and Inflationary Transmission

The Red Sea is a critical corridor for oil and LNG shipments. Risk premiums have increased global energy prices, transmitting inflation into South Asian economies dependent on fuel imports.

This has forced governments and central banks into difficult trade-offs between inflation control and growth support.

Geopolitics and Supply Chain Resilience

The crisis exposes the fragility of globalization in an era of geopolitical fragmentation. South Asia must invest in port efficiency, regional trade integration, diversified corridors, and multimodal logistics.

Economic development is now inseparable from maritime security and geopolitical strategy.

Conclusion

The Red Sea crisis has evolved into a systemic economic shock for South Asia. Rising logistics costs, delayed exports, and inflationary pressures show how deeply trade is now intertwined with geopolitical stability.

For Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, building resilience through infrastructure investment, trade diversification, and security cooperation is no longer optional—it is essential.

Saif Ali

Mukhtiarkar CCE-2020